When inherited mineral rights or family gifts become part of divorce property disputes, how much documentation is enough to prove separate property? A recent Austin Court of Appeals decision in this case (July 2025) answers this question with significant implications for Dallas-area couples who own inherited assets, mineral interests, or property acquired through family transactions. This case demonstrates that even testimony from multiple family members combined with expert tracing analysis may prove insufficient when the documentary evidence contains gaps.

Per the published opinion, the court’s holding reinforces that Texas law requires clear and convincing documentary evidence to overcome the presumption that property held during marriage is community property, and that testimony alone, regardless of how credible, cannot substitute for complete financial documentation showing the chain of title from inception to the asset in question.

Background: A Father’s Gift and Missing Documentation

M.O. and S.O. married in 1995 and built a life together for nearly three decades. In April 2009, M.O.’s mother passed away, and his father became trustee of a trust established in her name. The trust held mineral interests in land in McMullen County, Texas, valuable assets that would become central to the couple’s divorce proceedings years later.

On November 1, 2009, M.O.’s father, acting as trustee, prepared a “Mineral Deed” transferring mineral interests to M.O. and his five siblings in equal shares. Critically, the deed stated that “for an adequate consideration paid and received,” the grantor “grants, bargains, sells, conveys and transfers” the mineral interests. This language, reciting a sale for consideration rather than a gift—would prove decisive in the trial court’s analysis.

M.O. testified that a few days after the deed’s effective date, his father gifted each sibling $12,000 from their mother’s estate with instructions to use that money to purchase the mineral interests from the trust. The documentary evidence M.O. presented to support this narrative included a carbon copy of a check dated November 19, 2009, for $12,000 payable to M.O., but this carbon copy lacked the payor’s name, signature, or account number. The evidence also included a bank statement for M.O. and S.O.’s joint account showing a November 23, 2009 deposit of $12,171 and a December 3, 2009 check for $11,130.50, but these entries didn’t show who made the deposit, the source of the funds, or the recipient of the check.

M.O.’s sister corroborated his account, testifying that she and her siblings obtained equal shares of mineral interests when their father gifted them $12,000 and directed them to deposit that money and write a check for slightly over $11,000 to their mother’s trust to purchase the interests. S.O. testified that “it looks to be the case” that M.O. used the $12,000 check to purchase the mineral interests, but also stated “I don’t know what the purpose of [the $12,000 check] was” and “I am not disputing that the 12,000, or that was a purchase of mineral rights, given the exhibits that we have. I don’t know the nature of what went into that.”

M.O. testified he created entities and opened bank accounts to segregate the mineral interests and other inherited property, plus the income they produced, from the community estate. He produced an expert witness who testified about tracing various assets from that seed money as separate property. S.O. produced her own expert who testified that the tracing of the mineral interests as separate property failed and thus the mineral interests and all income and proceeds growing from them were community property.

The trial court determined that the mineral interests conveyed to M.O. were part of the community estate. Critically, the court found that the deed’s language indicated the mineral-interest transfer was complete on November 1, 2009, for “adequate consideration [paid] and received”—meaning any subsequent financial activities with the $12,000 check occurred after the transaction was already completed. The court also found M.O.’s testimony about the financial activities related to the $12,000 check was not credible.

The trial court’s characterization of the mineral interests as community property had enormous consequences: the reconstituted community estate comprised more than $10 million with the inclusion of the proceeds from the mineral estate, resulting in an award to S.O. of a much larger amount than M.O. considered her just and right share of what he believed was the properly constituted community estate.

The Court of Appeals’ Analysis: Documentation Trumps Testimony

M.O. appealed, raising three primary arguments: (1) the trial court erred by excluding evidence of his father’s donative intent; (2) the court failed to consider the presumption that parent-to-child transfers are gifts; and (3) the court failed to consider all applicable tracing methods for establishing separate property.

Exclusion of Evidence: Preservation Failures

M.O. first argued the trial court erred by refusing to admit Exhibit 7—a handwritten note from his father dated September 6, 2012, discussing financial transactions related to estate planning. M.O. sought to introduce this evidence to corroborate his tracing evidence and overcome the Dead Man’s Rule, which prohibits uncorroborated testimony about oral statements made by a decedent.

However, the Court of Appeals held that M.O. failed to preserve this issue for appeal. To preserve a claim of error in evidence exclusion, the proponent must inform the court of the substance of the evidence through an offer of proof unless the substance was apparent from context. The party must present the evidence’s nature with enough specificity that both the trial court and appellate court can assess its admissibility and whether any exclusion was harmful.

The court found that M.O.’s testimony about Exhibit 7 described only the general type of information it contained (transactions and estate planning) but not the substance of its contents (what the specific transactions and intent were). This testimony merely “comment[ed] on the reasons for” admitting the exhibit but did not “describe the actual content” as required to preserve error. Without knowing what the exhibit would have shown, the appellate court could not assess whether its exclusion was harmful.

The Parental Gift Presumption: Rebutted by the Deed’s Language

M.O. argued the trial court failed to consider the presumption that parent-to-child transfers of property are gifts, which should have characterized the mineral interests as his separate property. Texas law does create such a presumption—when a person conveys property to a natural object of the grantor’s bounty (such as a parent to child), it creates a rebuttable presumption of a gift.

However, the Court of Appeals found legally and factually sufficient evidence to support the trial court’s determination that this presumption was rebutted by clear and convincing evidence. The deed itself stated the mineral interests were sold for “adequate consideration paid and received.” M.O.’s own testimony and that of his sister and expert all described the transaction as a “purchase” of mineral rights using the $12,000. As the court reasoned, if the deed were a gift, these purchase transactions would have been unnecessary.

The court distinguished this case from J. v. P., where a gift presumption prevailed because there was no evidence the consideration stated in the deed was actually paid. Here, M.O.’s own evidence indicated consideration was indeed paid, just potentially after the deed was executed, which created problems for his separate property claim.

Tracing Requirements: Clear Documentary Evidence Required

The heart of the case involved M.O.’s attempt to trace the source of funds used to purchase the mineral interests as separate property through various tracing methodologies: the community-out-first method, the clearinghouse method, and the identical-sum-inference method.

Community-Out-First Method: Under this approach, when separate and community property are commingled in a single bank account, courts presume community funds are drawn out first before separate funds are withdrawn. The only requirement is that the party overcoming the community presumption produce clear evidence of transactions affecting the commingled account.

M.O.’s own expert initially testified the record prevented him from using this method for the mineral interests purchase. When pressed, the expert acknowledged he lacked bank statements showing where the $12,000 “went in and went out” and could not trace the funds. S.O.’s expert testified that even applying this method, the $11,130.50 check would still be community property because there was insufficient support showing the $12,171 deposit contained any separate property component.

Clearinghouse Method: This method applies to exceptional items within broader community-out-first tracing. It presumes that when a spouse deposits separate property into a commingled account and makes a subsequent purchase of a similar amount from that account within a short time, the purchased asset may be traced as separate property.

The court noted cases where courts have applied this method even when deposit and withdrawal amounts differ slightly, such as Estate of H. v. H. (deposit of $6,021, withdrawal of $6,170 same day) and H. v. H. (deposit of $91,200, immediate withdrawal of $90,000). However, those cases involved either no commingling or immediate transfers, and importantly, documentation of the tracing wasn’t disputed on appeal.

Here, separate funds had been commingled with community funds, there was a ten-day gap between deposit and withdrawal, and critically, M.O. lacked documentation showing: (1) the payor and account number that were the source of the $12,000 check; (2) the source of funds comprising the $12,171 deposit; and (3) the recipient of the $11,130.50 check.

Identical-Sum-Inference Method: This variation of the clearinghouse method involves a single deposit and single withdrawal of identical or nearly identical amounts. The trial court found this method inapplicable because there were at least three unequal sums: $12,000 (check), $12,171 (deposit), and $11,130.50 (withdrawal).

More fundamentally, the same tracing deficiencies that defeated the clearinghouse method also defeated the identical-sum-inference approach, namely, lack of documentation establishing the source of the check, proof that the deposit was separate funds, and evidence that the check was used to purchase the mineral interests.

The Fundamental Problem: Incomplete Documentation

The Court of Appeals emphasized that Texas law requires documentary evidence, not merely testimony, to trace separate property by the clear and convincing standard. Even when testimony indicates property was purchased with separate funds, “without any tracing of the funds from their inception to the relevant purchase,” such testimony alone is insufficient to rebut the community property presumption.

The court cited G. v. V., where a husband failed to overcome the community property presumption for retirement and brokerage accounts because neither his testimony nor exhibits provided “statements of accounts, dates of transfers, amounts transferred in or out, sources of funds, or any semblance of asset tracing.” Similarly here, critical documentation was missing: the $12,000 carbon check lacked payor information, the deposit slip didn’t show the source of funds, and the bank statement didn’t identify the check’s recipient.

Key Takeaways for Dallas Divorcing Couples

The decision offers critical lessons for individuals with inherited assets or family-gifted property:

Documentation Is Essential: Testimony from family members and even expert witnesses cannot substitute for complete financial documentation. Carbon copies of checks without payor information, bank statements without deposit sources, and transaction records without payee identification create fatal gaps in separate property tracing.

Deed Language Matters: When a deed recites “adequate consideration paid and received,” that language can rebut the presumption that parent-to-child transfers are gifts, even when the parties’ intent was to structure a gift.

Timing Creates Complications: When a deed is executed before the purported consideration is paid, courts may find the transaction was complete when the deed was executed, making subsequent payments irrelevant to the characterization.

Preservation Requires Specificity: To preserve error regarding excluded evidence, parties must make offers of proof that describe the actual content of the evidence—not merely the type or purpose of the evidence.

Strategic Considerations in Inherited Property Cases

What we’ve learned from this case is the critical importance of meticulous documentation when acquiring property during marriage that a spouse intends to remain separate. Different approaches might have included having M.O.’s father structure the transaction differently, perhaps executing the deed only after receiving the $12,000 payment, or clearly documenting the deed as a gift rather than a sale.

Alternative strategies could have addressed the evidentiary gaps more comprehensively. Rather than relying on carbon copies and incomplete bank statements, different preparation might have included obtaining: certified copies of the actual check with account numbers and signatures; deposit slips showing the source of the $12,171 deposit; cancelled checks or wire transfer receipts showing the $11,130.50 payment went to the trust; and contemporary correspondence documenting the father’s intent to gift funds for the purchase.

For those working with a Dallas family law attorney, this case demonstrates why proactive estate planning and asset protection during marriage, not just during divorce, is essential. Experienced counsel can help structure inheritance receipts, family gifts, and asset purchases to maintain clear separate property character from the outset, rather than attempting to reconstruct that character years later during divorce proceedings.

Protecting Inherited Assets in Divorce

Divorce cases involving inherited property, mineral interests, or assets acquired through family transactions require extraordinary attention to documentation and tracing from the moment the asset is received. The case decision makes clear that Texas courts will not accept testimony alone, regardless of how many family members corroborate the account or how qualified the expert witness may be, when the financial documentation contains gaps.

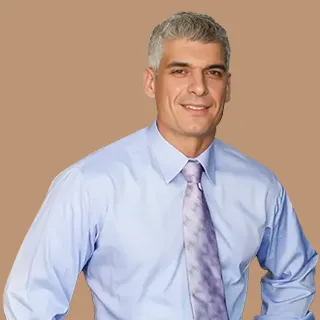

At our Dallas family law practice, we bring over 25 years of experience handling complex property divisions involving inherited assets, mineral rights, and challenging separate property tracing issues. We serve clients throughout the Dallas metropolitan area, including Irving, Richardson, Garland, Mesquite, DeSoto, Grand Prairie, Lakewood, Highland Park, Cockrell Hill, Lancaster, Seagoville, and Duncanville.

We understand that inherited property and family gifts represent not just financial value but also emotional connections to family legacy. When these assets become subject to division in divorce, the financial and emotional stakes are high. Proper characterization requires both thorough documentation and strategic presentation of that documentation to satisfy Texas’s demanding clear-and-convincing-evidence standard.

If you own inherited property, mineral interests, or assets acquired through family transactions and are considering divorce, or if you’re already in divorce proceedings involving such assets, we provide honest assessments grounded in realistic expectations based on current Texas law. We can evaluate the strength of your documentation, identify gaps that need to be addressed, and develop strategic approaches to protect your separate property interests.

Don’t risk losing inherited assets due to insufficient documentation or improper tracing. Contact us today to learn more about how our comprehensive divorce services can help you protect family property in divorce proceedings. For a Dallas divorce attorney consultation focused on your specific asset protection needs, call our office or visit our contact page to begin the conversation about safeguarding your inherited property.

Learn more about our approach to family law and how we can help you navigate separate property tracing and complex asset characterization with both strategic precision and attention to preserving family legacies. Whether you need guidance on property division matters or comprehensive divorce advocacy, we’re here to provide the experienced representation you deserve as a trusted divorce attorney near me for Dallas-area residents facing these challenging circumstances.