When a Dallas Divorce Attorney Must Challenge an Overreaching Court Order

Divorce doesn’t end when the judge signs the final decree. For many Dallas couples who co-own businesses or have complex asset divisions, the real legal battles often emerge years later during the enforcement phase. A recent Texas appellate decision, A.W.E. v. D.M.F.N. (2025), offers crucial insights into how far trial courts can go when enforcing divorce decrees, and what happens when those orders exceed their authority.

Per the published opinion, this case illustrates why experienced Dallas divorce attorney representation matters not just during the initial divorce, but throughout the post-decree enforcement process. The Court of Appeals reversed a comprehensive temporary injunction that had been granted to prevent one former spouse from filing lawsuits, exposing significant vulnerabilities in how the trial court approached enforcing a prior decree ordering the sale of a jointly-owned company.

For Dallas-area residents navigating post-divorce disputes or facing court orders that seem to restrict your legal rights, understanding this case can help you evaluate whether your situation might benefit from appellate review or a direct challenge to an order.

Background: When a Divorce Decree Leaves Loose Ends

A.W.E. and D.M.F.N. divorced in October 2019 in Dallas County’s 254th Judicial District Court. Like many divorces involving business assets, their Final Decree of Divorce included detailed provisions about what should happen to property they co-owned: a consulting, brokerage, and technology solutions company serving corporate real-estate clients.

The decree ordered that the company be sold and appointed M. Partners as the entity responsible for carrying out that sale. This provision remained unchanged when the Final Decree N.P.T. was entered in 2020. The decree seemed clear, the company would be sold, and the parties would receive their respective proceeds.

Yet five years after the divorce, the company had not been sold.

A.W.E. disagreed with how the post-divorce situation had developed. She had previously appealed the property division aspect of the divorce decree, but the Dallas family law court affirmed the original decree in 2021. She also filed a separate lawsuit alleging that D.M.F.N. and others had engaged in breach of fiduciary duty and fraud, claims that remained pending in federal court.

Meanwhile, around August 2024, D.M.F.N. decided to take action. He filed what’s called a “post-decree enforcement proceeding” under Texas Family Code Chapter 9, arguing that A.W.E. had failed to comply with the sale provision. The trial court quickly granted temporary measures, including appointing a receiver to handle the sale and issuing various temporary injunctions against A.W.E.

The tension escalated in September 2024 when A.W.E.’s attorney sent a “litigation hold letter” to a competitor of the company. This letter asserted that A.W.E. “was wrongfully ostracized from her own companies” and indicated that “anticipated litigation” concerning “unlawful conduct” involving “improper diversion, misclassification, and misallocation of commissions, fees, and assets” would commence. The letter referenced a pattern of activity spanning from January 2015 onward.

This litigation hold letter, sent to fifty-one recipients including prospective buyers and some of the company’s largest clients, became the catalyst for the injunction that would ultimately be reversed.

The Trial Court’s Response: An Extraordinary Temporary Injunction

On November 15, 2024, the trial court signed what it called an “Additional Temporary Injunction.” This eight-page order went significantly beyond typical post-decree enforcement measures.

The injunction prohibited A.W.E. from “filing lawsuits individually, whether in Texas or outside Texas, against the Company, a Receiver duly appointed by the Court under this Cause Number, or any employee, officer, director, client, and/or potential client of the Company without approval of the Company’s Board of Directors or without giving the Company’s Board of Directors a chance to hear and investigate the basis of any potential lawsuit.”

To understand how broad this actually was, consider what it meant in practice. A.W.E. could not file any lawsuit, whether in state court or federal court, against numerous categories of people and entities without first securing board approval or allowing the board to investigate. The order didn’t require her to identify which clients or employees she was prohibited from suing; it simply said “clients” and “potential clients” without listing them.

The trial court’s reasoning, as stated in its written findings, was that:

The company was actively being marketed for sale by a court-appointed receiver. The litigation hold letter had caused at least one prospective buyer to lose interest in purchasing the company. If A.W.E. filed lawsuits involving company employees, officers, or clients, she might disclose confidential company information to competitors or the public, harming the company’s sale value. A “tolling agreement” concerning A.W.E.’s existing federal court litigation was set to expire on November 7, 2024, suggesting she was likely to file additional suits. Allowing lawsuits to proceed would impede the receiver’s efforts to sell the company as ordered in the divorce decree.

The trial court found that imminent, irreparable harm would result without the injunction and waived the bond requirement that would normally be required when issuing a temporary injunction.

Legal Analysis: Where the Trial Court Exceeded Its Authority

When A.W.E. appealed this injunction, the Dallas Court of Appeals panel, composed of Justices Rosenberg, Clinton, and Lee, found multiple legal problems with the order. Their analysis is essential for understanding the limits of judicial power in post-decree enforcement proceedings.

Issue One: Restraining Federal Court Access

The first and perhaps most clear-cut error involved federal court jurisdiction. The injunction prohibited A.W.E. from filing lawsuits “in Texas or outside Texas” without board approval. This language captured both state court and federal court proceedings.

Here’s the problem: A Texas state court simply cannot enjoin a party from filing or continuing proceedings in federal court. This is an “old and well-established judicially declared rule,” the appeals court noted, citing the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Donovan v. City of Dallas, 377 U.S. 408 (1964).

The Supreme Court in Donovan made clear that the rights conferred by Congress to bring in personam (personal) actions in federal courts are not subject to abridgment by state-court injunctions, regardless of whether the federal litigation is already pending or merely prospective. A more recent Supreme Court case, General A. Co. v. F., 434 U.S. 12 (1977), reiterated that “it is clear from Donovan that the rights conferred by Congress to bring in personam actions in federal courts are not subject to abridgment by state-court injunctions.”

Texas courts have consistently applied this principle. As the Texas Supreme Court stated in Ex parte E., 939 S.W.2d 142 (1997), “It is settled that ‘state courts are completely without power to restrain federal court proceedings in in personam actions.'”

The appellate court sustained A.W.E.’s first issue, ruling that the temporary injunction was void to the extent it enjoined her from filing an in personam action in federal court. D.M.F.N. actually conceded this point, acknowledging that the injunction was “defective to the extent it enjoins [A.W.E.] from filing suit in federal court.”

What this means for Dallas divorcing couples: If your divorce decree gives one spouse concerns about federal claims, a state court cannot use an injunction to prevent you from pursuing those federal claims. Federal jurisdiction is protected.

Issue Two: The Bond Requirement Under Civil Procedure Rule 684

Texas Civil Procedure Rule 684 states clearly: “In the order granting any… temporary injunction, the court shall fix the amount of security to be given by the applicant.” Security, in this context, means a bond, money put up by the person seeking the injunction to compensate the other party if the injunction turns out to have been wrongly granted.

This requirement exists for a reason: injunctions are extraordinary remedies. Making the applicant post a bond ensures that they have genuine skin in the game and discourages frivolous requests for injunctive relief.

The trial court simply waived this requirement without following the rule. D.M.F.N. argued that Civil Procedure Rule 693a should apply instead. Rule 693a states: “In a divorce case the court in its discretion may dispense with the necessity of a bond in connection with an ancillary injunction in behalf of one spouse against the other.”

But here’s the critical distinction: This was not a divorce case. A.W.E. and D.M.F.N. had already been divorced since 2019, this was a post-decree enforcement proceeding under Texas Family Code Chapter 9. Rule 693a specifically applies “[i]n a divorce case.” Once the divorce is final, that rule no longer applies.

The appellate court cited multiple precedents confirming that Rule 693a does not extend beyond the divorce proceeding itself. In L. v. L., 291 S.W.2d 303 (1956), the court noted that Rule 693a “specifically requires the giving of an injunction bond prior to the issuance of an injunction” and concluded that an injunction was void because no bond was required as a condition precedent to its issuance.

The court also cited E. v. H., 814 S.W.2d 179 (1991), where the Houston Court of Appeals stated: “The suit was not a divorce case, nor were the parties presently spouses and stating, ‘[R]ule 693a is inapplicable.'”

What this means for Dallas family law: Post-divorce proceedings are treated differently than divorce proceedings themselves. The protections and exemptions available during a divorce divorce don’t automatically carry over into post-decree enforcement. When facing a temporary injunction in a post-decree matter, insist that proper bonds be required.

Issue Three: The Lack of Specificity Required by Rule 683

Texas Civil Procedure Rule 683 requires that a temporary injunction order “shall be specific in terms; [and] shall describe in reasonable detail and not by reference to the complaint or other document, the act or acts sought to be restrained.”

The reason for this rule is straightforward: a party must know exactly what conduct is prohibited. Vague or overbroad injunctions violate due process principles and practical fairness. How can A.W.E. comply with an order if she doesn’t know whether she’s violating it?

The injunction in this case referred to prohibiting suits against “any employee, officer, director, client, and/or potential client of the Company.” But A.W.E. had not been included in company matters since 2018. She didn’t know who the current clients were. She didn’t know who the “potential clients” might be. She knew that FedEx had been a long-term client “for many decades,” but she testified that she didn’t know if FedEx was still a client.

The appellate court found this violated Rule 683’s specificity requirement. The court cited C. C. & O. S., Inc. v. W., 156 S.W.3d 217 (2005), a Dallas Court of Appeals decision involving a permanent injunction that prohibited a company from doing business with clients who were not specifically listed.

In C., the court held: “The injunction itself must provide the specific information as to the off-limits clients, without inferences or conclusions.” A.W.E. provided a hypothetical that illustrated the problem perfectly: under the trial court’s order, she could theoretically violate the injunction by filing a personal injury lawsuit against someone involved in a collision with a FedEx truck, even though such a claim would have nothing to do with the company or the divorce dispute.

What this means for Dallas residents: Injunctions must be specific enough that you can actually comply with them. If you’re facing an injunction that relies on undefined terms like “potential clients” or “related parties,” that’s a strong basis for appeal or modification.

Issue Four: The Fatal Flaw, No Evidence of Imminent, Irreparable Harm

This issue struck at the heart of whether a temporary injunction should have been granted at all. To obtain a temporary injunction, the applicant must show: (1) a cause of action against the party to be enjoined; (2) a probable right to recover on that claim after trial; and (3) a probable, imminent, and irreparable injury absent the temporary injunction.

The appellate court focused on whether there was actual evidence of (3), imminent, irreparable harm.

The trial court had found that A.W.E. was “on the verge of commencing litigation” and that “harm to D.M.F.N. and to the Company is imminent.” But what did the actual evidence show?

The Receiver testified that he had a present expectation of the company’s value before the anticipated litigation, could quantify the difference between the anticipated sale price and the actual sale price once it sold, and that this difference “will be measured in dollars and cents.” This testimony actually undercut the trial court’s conclusion. If the harm can be measured in dollars and cents, in specific monetary damages, then by definition the harm is not “irreparable.”

Texas courts define “irreparable harm” as harm that cannot be adequately compensated in damages or that the damages could not be measured by any certain pecuniary standard. If you can measure the loss in dollars, it’s not irreparable under Texas law. The H.C.P.., 690 S.W.3d 32 (2024), decision makes this clear: “An irreparable injury exists if the party injured cannot sufficiently be compensated in damages or the amount of damages is immeasurable by pecuniary standards.”

Furthermore, the appellate court noted that there was no actual evidence of an imminent state court lawsuit. The only lawsuit that could have been enjoined by a state court injunction would be a state court lawsuit, not a federal court case. A.W.E. had a tolling agreement regarding federal litigation that was set to expire November 7, 2024, but tolling agreements typically preserve claims without them being deemed abandoned. The court found no evidence that A.W.E. had actually filed or was imminently about to file a state court lawsuit.

The litigation hold letter, while concerning to D.M.F.N., was not the same as an actual lawsuit. It was notice of potential claims. In the appellate court’s view, potential harm from potential lawsuits particularly when there was no evidence any state court lawsuit had been filed, was not sufficiently imminent to justify an injunction.

What this means for Dallas divorce enforcement proceedings: The trial court cannot issue injunctions based on speculation or general concern. There must be specific, concrete evidence of imminent harm. If your former spouse is seeking an injunction against you, ask: what exact harm will occur if this injunction is not granted? Can that harm be measured in dollars? Is there real evidence of an imminent violation, or just concern about what might happen?

Strategic Considerations: Alternative Approaches in Post-Decree Disputes

While the appellate court did not criticize any attorney’s performance, it was focused on the trial court’s legal errors, the case does illuminate some strategic considerations that might arise in similar situations.

When enforcement proceedings involve business disputes and potential litigation, the parties and their counsel must balance several competing interests. D.M.F.N. wanted to protect the company’s sale value and prevent A.W.E. from derailing the sale process through litigation. That interest was legitimate. A.W.E. wanted to preserve her right to pursue what she believed were meritorious claims for breach of fiduciary duty and fraud.

Different strategic approaches might have included: (1) negotiating a stay of A.W.E.’s existing federal litigation for a specific, limited time period while the company sale proceeded; (2) seeking a more narrowly tailored injunction that specifically prohibited conduct directly related to the sale (such as contacting prospective buyers), rather than restricting her right to file lawsuits; (3) addressing the company sale through other mechanisms, such as having the receiver sell with court approval before any litigation could disrupt the process; or (4) negotiating a settlement of the underlying federal litigation claims as part of resolving the post-decree dispute.

Each approach would have involved different trade-offs, and the best choice would have depended on the specific circumstances, settlement postures, and litigation risks that existed at the time.

Key Takeaways for Dallas-Area Divorcing Couples

If you’re dealing with post-decree issues, whether involving business assets, child support modifications, property division disputes, or ongoing enforcement matters, this case offers several important lessons.

First, post-decree proceedings are not the same as divorce proceedings. The procedural rules are different, and exemptions that applied during the divorce may not apply afterward. When a best divorce lawyer in Dallas represents you in post-decree matters, they must be equally vigilant about procedural compliance as during the initial divorce.

Second, extraordinary remedies require extraordinary justification. Injunctions are not routine tools. Courts must have clear, specific evidence of imminent, irreparable harm before granting them. If you face an injunction, scrutinize whether the evidence actually supports the conclusions the trial court reached.

Third, specificity matters. Vague injunctions are unenforceable and vulnerable to appeal. If you’re seeking an injunction (or defending against one), make sure it describes with precision what conduct is prohibited and what conduct is permitted.

Fourth, federal court access cannot be blocked by state courts. If part of your divorce dispute involves federal claims—whether under federal employment law, securities law, or other federal statutes, state court injunctions cannot restrict your ability to file in federal court.

What This Means for Your Situation

If you’re navigating post-decree enforcement in the Dallas area—including Irving, Richardson, Garland, Mesquite, DeSoto, Grand Prairie, or surrounding communities, these legal principles directly apply to your case. Whether you’re the person seeking to enforce a decree or defending against enforcement efforts, understanding how appellate courts review these orders is essential.

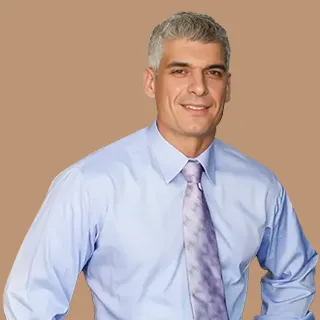

At our firm, we have 25+ years of experience handling Dallas family law matters, including complex post-decree disputes. We provide honest assessments of your situation rather than false promises about outcomes. If you face a temporary injunction that seems overbroad, if you’re concerned that your legal rights are being restricted unfairly, or if you’re uncertain how to proceed with post-decree enforcement, we can evaluate your specific circumstances and explain your options.

We understand that divorce doesn’t end when the judge signs the decree. Our Dallas family law attorney team takes a strategic approach balanced with compassion for clients navigating these complex proceedings. We serve Dallas and the surrounding areas including Irving, Richardson, Garland, Mesquite, DeSoto, Grand Prairie, Lakewood, Highland Park, Cockrell Hill, Lancaster, Seagoville, and Duncanville.

Whether you need a Dallas divorce lawyer consultation about a post-decree issue, advice on enforcing an existing decree, or representation in challenging an order you believe exceeds the court’s authority, we’re here to help. Contact us today to discuss your specific situation. With 25+ years of Dallas family law experience, we know how to protect your rights while working toward practical, sustainable solutions.